At fifteen pages, it was far too long to include with the newsletter, but I thought it might be of interest to some people, and I've a bad habit of sitting on writings like this until they're no long indicative of my thoughts on any subject and thus unpublishable. One of the things I hope to do in the coming months is use what time my new schedule will permit me (though I'm not on that schedule yet!) to better present that which I've done and which only a handful of folk usually see or hear. This is long; hopefully, you'll find it interesting.

Benjamin Franklin's Pants

My name is Chris Schweizer, and I’m a cartoonist. I’m sure that all of you have heard of this job, but may not know exactly what it entails. A comic writer comes up with stories for comics, and writes the script; a comic artist takes that script and draws it out in comic form. A cartoonist is someone who both writes and draws a comic, whether for newspapers, comic books, or, as is more often the case these days, book-length comics which have come to be known as “graphic novels.” Though I’ve dabbled in the other two, this last format is where I do most of my work. And the graphic novels that I make are historical fiction.

Today, I’d like to talk a little about approaching historical fiction in general, and use my experience working on these books to talk about a few points specifically, notably the difficulty that can arise when trying to find visual reference. This can be especially trying if you work in comics, animation, illustration, preproduction, or costume design, though a writer inclined towards description might find him or herself equally vexed. I am by no means an expert on historical fiction, though I do read a lot of it, and I am no master when it comes to its execution; my books are certainly flawed, though my hope is to make each book a little less so than the last. I beg your indulgence and patience, and thank you all for coming out today, and ask that you save any questions until the end.

When writing historical fiction, research is your most important tool. It doesn’t matter if you’re writing a novel, a comic, a play, or a film – simply setting the story in a clearly discernible past requires you to have a familiarity with that past, and to use it to help craft your story.

There can be a tendency among authors, especially ones who are natural storytellers, to want to plot first and fill in the necessary period details afterwards. I caution you against approaching your story this way. If the process is not always evident to the audience, its outcome is – stories that are generic, draped in the trappings of the period in which they purport to take place but with none of its flavor, its charm, its horror, or its social root.

Though even a passing familiarity with history will attest to the consistency of the human spirit and its capacity for both great benevolence and terrible cruelty, the rules governing society change rapidly from place to place and time to time. People continue to behave as they have always behaved. I like to delude myself into thinking that we are somewhat better than our predecessors, that we are wiser, kinder, more just. Reading the same self-congratulatory appraisals from every era that has come before alerts me to my foolishness, but it’s one of those faiths that facts cannot truly shake away. The reality is that people are consistent. Some may be more compassionate or forward thinking than others, but a mix of social morays, personal morality, and pragmatism has always been the cocktail that drives the overwhelming majority of human behavior, and those considerations are clearly and decisively shaped by the time and place in which a person finds him or herself.

Therefore, the actions taken by your characters, and the situations that require these actions, must derive from the conditions of existence in that setting. This holistic approach to historical narrative has been a staple of the genre since the nineteenth century, when writers like Walter Scott, Victor Hugo and Alexander Dumas brought the period piece into full flower.

By addressing how the characters in their stories naturally reacted to the peculiarities of their own time, the authors could show that genuine humanity, and draw attention to the differences between the time of the story and that of the reader. This creates a much longer shelf-life for the true period stories than those simply taking place in the past. One can watch Richard Lester’s adaptations of Dumas’ Three Musketeers and still be entertained and constantly surprised by the hundreds of details in which he clearly showed the differences between the 1620s and the 1970s.

The cast of the Lester adaptation, clockwise from upper left: Oliver Reed as Athos, Frank Finlay as Porthos, Richard Chamberlain as Aramis, Michael York as D'Artagnon, Charlton Heston as Cardinal Richelieu, and Christopher Lee as the Comte d'Rochefort.

Nearly forty years later, those differences still pop (we are no closer to the 1620s that was Lester’s original audience), and this helps to make those films an exciting and engaging watch; the same cannot be said for the 1993 version starring Keifer Sutherland and Charlie Sheen. It is an excellent example of everything that can be done wrong with a period piece, using only the loosest possible impression of the time as its setting and creating a hackneyed, uninspired piece that does not stand up at all to rewatching.

The Disney version, complete with costumes so seaped in genericism you'd swear they were stolen from a high school theater department

There was another terrible musketeers film around 2000, and another on the horizon. Lester’s piece was fresh and of its time, appealing to the Beatles crowd and the Monty Python set. Giving your work a contemporary and hip approach doesn’t mean throwing history out the window; the ones that do find themselves passed over in the three-dollar bin at Big Lots, the ones that stay true still find an audience. It’s not hard to tell which directors did their research.

Research, for me, is the hardest part of my job. Not that I don’t love doing it; I do. And no one period holds my interest, though I do tend to obsess over one for a while and then move on to another. This works very well for me, as the structure of my books demands it. The Crogan Adventures, which is the series’ name, is a bit of an unusual mold for a historical series. Each book features as its protagonist a different member of the fictitious Crogan family paternal line at different points throughout its history. The first book was a pirate story, the second a tale of the French Foreign Legion in North Africa. The third book, which I hope to complete by summer’s end, is the story of two brothers fighting on different sides of the American Revolution.

I feel amazingly fortunate to have stumbled into the idea for this series, considering my wandering eye. I can thoroughly exhaust a subject and move on to another, and while I love this, is does have one significant drawback. As I am approaching a new time period with each book, my research for the series cannot simply build on what I have already learned, as is the case with most people employing the series format. I have to start from scratch, using what little knowledge I possess of the new subject to find books and films and novels and articles through which I might better my understanding and build a foundation for my story.

I spend roughly six months researching. The first is usually hard, the sixth harder. The first is frustrating. Not knowing where to begin. Not knowing anything. Having to consume book after book in order to get enough of a basis to start looking for the specifics which I expect my story might utilize.

After this, it’s wonderful. I’m designing my characters, I’m thinking loosely about my plot, I’m learning new and pertinent information about a subject for whom my enthusiasm is growing and growing.

And that enthusiasm is why it gets harder and harder. I become so anxious to start undertaking my story in earnest that the research becomes a chore, something I have to get past before I can work. It is especially difficult because I work best when able to observe how far I have gone, and research yields intangible results. There is no stack of pages of which I can be proud; there is only slowly – so, so slowly – growing knowledge, and I cannot chart its growth, especially as I likely forget something else along the way.

But this long period of research, done before attempting to craft the narrative, is essential for two primary reasons.

The first is familiarity. How many of you could, if pressed to do so, write a short story taking place in your high school, back when you attended? Regardless of the story’s genre, you probably know your high school well enough that you could come up with the story without having to revisit the building or read up on the school’s history. You could certainly check a few facts and figures afterwards, but you have enough familiarity with the setting to believably place your story there.

That is what a steady, immersive approach to research offers: a familiarity with the period. Your ideal with your research is to never need to touch a reference book while you’re writing. You’ll have to, of course, but that’s the ideal. You want to have that familiarity, so that you needn’t stop to look up whether or not there was electricity west of the Mississippi in 1872, or who was Queen of England in 1588, or whether folks in colonial Maine were more inclined to tea or coffee. You’ll know these things. You can approach your story with the confidence of someone as familiar with his or her setting as you are with memories of your high school, or office, or whatever you might know well. This confidence is important. Having to check facts at every instance will leave you frustrated. It will create dead ends for your story, as you lead your characters towards points deemed impossible by history, forcing you to go back, over and over again, and most of all it will never allow you to get momentum as a writer, and without that momentum your story will feel fragmented and you will hate the act of writing it.

The other primary reason that preemptive research is a must is that it will inform the direction that your story takes. This is what sets apart what I called “real period pieces” from stories that simply happen to be set in the past. The latter is a flat tale that could be picked up and dropped anywhere – the ancient Roman countryside, medieval England, the American prairie. That is not to say that there cannot be good stories that are at home in more than one place or time. There can be. And there will always be elements of one historical period that mirror another so well that the two could easily interchange.

The Seven Samurai and The Magnificent Seven

The American West and the late medieval Sengoku period of Japan have enough in common as to allow their stories to hop back and forth with great regularity. In order for this sort of thing to work, however, there needs to be a striking similarity in the social order. Casablanca, for example, is a story taking place in a country occupied by an oppressive, sometimes ruthless regime, in a city known more for its huge flux of foreign interests, expatriates, and refugees than any indigenous population, on the eve of war. Spies and intrigue abound, and there is a general romantic exoticism that permeates. A very specific list of circumstances, but one that fits Shanghai in 1930 just as well as it does Casablanca in 1941.

Sometimes there will be a span of hundreds of years between suitable social mirrors. There are striking similarities between the outcomes of the Russian and French revolutions. The lot of a pressed seaman in Napoleonic times may not differ much from a young man drafted to Vietnam, if the story’s focus is the bitter separation from a loved one and life’s previous expectancies. But it is not often that these opportunities to take one story to many places arise, and if one is to recognize those opportunities one must do the same research.

When the research is not done, one gets a generic story, usually action or romance, and relates it to its environment peripherally at best. Westerns, medieval films, World War II stories… some are statistically guiltier of this than others. With any story, the setting should play a part. It should affect the way your characters act, think, respond, and it should be a contributing factor in whatever situations they find themselves embroiled.

Researching does not mean reading only dusty tomes and dry nonfiction. You should immerse yourself in the period in whatever way you’re able. This includes, and necessitates, watching films set in this period, both good and bad.

Hollywood gets an unfairly bad wrap for playing fast and loose with history. I think that Hollywood is the best thing to ever happen to the study of history. For every one thing they get wrong, they get thirty right. Take the Ten Commandments. Demille’s employment of experts on all aspects of ancient Egyptian life, building, clothing, etc significantly expanded academic scholarship on the period, and brought it to vivid life before enraptured audiences. It doesn’t really matter if there weren’t Hebrew slaves that sounded like Edward G. Robinson, or that history tells us that the Hebrews may not have been slaves at all, but a dangerously-expanding population of emigrant mercenaries – we get a visceral, visual sense of what life was like in Ancient Egypt, for both the upper-tiers of royalty and the bottom rungs of servitude. The drama, the color, this is all secondary to the historical writer, for whom the vast scope is laid out in precious detail. Every year Hollywood releases at least one such film, a laboriously rendered reproduction of the past, and there is invariably a striking degree of accuracy. That the stories themselves might stray is important to note, but the trappings are, as a rule, quite sound. There are exceptions, of course – usually those aforementioned genres, as well as ones who willfully deviate for stylistic purposes – 300, for example, which ignores that the Spartans wore quite expansive armor and rarely moved in slow-motion.

Hollywood has, since its earliest days, had a fascination with the period piece. The capacity to fully reproduce another time is a great temptation, as you and I know, and many directors and producers have been unable to avoid it, for all the headaches it might cause. Many of the biggest money-losers in film history are period pieces, simply from the expense of trying to make them correct. Granted, you have B movies like Cornel Wilde’s Sword of Lancelot, which features bucket helmets and the immortal line “truly there has never been a kinglier man or a manlier king,” but contrast this against Lawrence of Arabia, Gangs of New York, Quo Vadis!, Demetrius and the Gladiators. And spectacle needn’t reign; there are many subtle pieces of much smaller scale that equally relate a clear sense of period – Robin and Marion and The Lion in Winter (the link of the latter is to a made-for TV version rather than the theatrical one; while the bleak and cold of the period and Henry II's downright meanness are better captured in O'Toole's incarnation, the performances are better in almost every case in the Stewart one) are two very small-scale medieval films that spring to mind (both happen written by James Goldman), and both do as good a job of capturing the sense of place and time as their more magnificent counterparts.

Watching these films – as well as reading novels either set in the period or written during it – is invaluable. It’s good to be a “method actor” of sorts when it comes to writing historical fiction. By immersing yourself entirely in it, it becomes what you know, what you think about. When my dreams start taking place in the period in which I’m working, I know that I’m the right frame of mind. It will help with the narrative, certainly, but also with how you tell the story: the characters will act the way that they should and the sentence structure and word choice in your dialogue will adhere to that used in its setting. But more important is a familiarity with the genre. Paraphrasing pop screenwriting teacher Robert McKee, a writer should have a knowledge of his or her genre that surpasses that of its audience.

I’ll see most any historical pirate movie that gets made. A lot of them are bad. Cutthroat Island, for example, is truly terrible. But I’ll still see it. I’ll see it four or five times, probably. And whatever the genre in which you find yourself working, there will be people who will see it simply because they are passionately enthusiastic about the subject, and not necessarily because they have an affection for your project specifically. And they will know their genre. They may not have actively studied it, or dissected what makes a film or novel or comic fall into that category, but they have a familiarity with it. You must, too. Partially, this is to ensure that you do not repeat something that has been done without realizing it. If you have a scene in your swashbuckler in which a pirate dives into the water to rescue a well-to-do girl, only to face imprisonment upon his resurface, you’ve failed in your job as a writer. This scene has already been done, and you should know that. You may want to do a variation on that scene, and such an approach would be fine, but only if you have that knowledge and can tailor into something that feels new.

But part of that genre familiarity is so that you CAN repeat certain things. In fact, you must. A western has to have a gunfight to work as a Western. If you present a Western and fail to include a gunfight, your audience will be furious. Does this mean you can’t set a story in the West without having a gunfight (usually as its climax)? No – you certainly can. But it will not be a western. There is, if I recall, only one gunfight in the whole HBO series Deadwood, and it happens in the first episode in order to alleviate the apprehension that would otherwise be felt by an audience expecting it.

There are certain genre conventions that must be adhered to for it to constitute, and find an audience. This doesn’t mean one needs to adhere to a rigid formula, or serve up a rehash of what’s been done. But it gives you a foundation upon which to build, and it is your job to meet these genre requirements – and historical periods DO often constitute their own genres, at least to me. Meet them, while subverting them, showing them in a new way, doing them with a new twist. Crafting your original story to allow it to work classically while being strikingly original is your goal. Again, this requires research. To cite the Western again, if you are doing a story in which a frontiersman is fighting plains Indians, it is your job to have watched the Searchers, Jeremiah Johnson, Lonesome Dove, its less-than stellar prequel Dead Man’s Walk, Little Big Man, Stagecoach, and a dozen others, probably many dozens. Working in a period in which there ARE a lot of novels or films taking place allows you a great deal of material from which you can spring, and I could not advise you more strongly to take advantage of that.

In the instances of both novels and film, it is your responsibility to track down the stories that may not be as readily available. Doing this sort of research has been a terrifying study in how quickly even popular works pass out of the public consciousness in a short amount of time. Terrifying because my stories are likely never going to be as engaging as theirs, and to see them fall more or less into obscurity bodes poorly for my own legacy. Raphael Sabatini, for example, was an adventure novelist working primarily in the early half of the twentieth century, with many of his most popular novels coming from the 1920s, 30s, and 40s: a relatively recent figure. As historical fiction, they are meticulous in their accounts. As fiction, they are engaging and exciting, full of romance and daring and excellent wordcraft.

But even though his work sold extremely well and was quite popular, spawning not only fans of his books but a number of films, including Captain Blood, Scaramouche, The Sea-Hawk, and the Black Swan, only three of his books were still in print as of a few years ago, and only one of these – Captain Blood – was easy to find. Thanks to devices like the Kindle, works such as these are coming back to availability, but finding which ones to read can be trying. Interviews, reference books, even seemingly cheap or juvenile books with titles like “The Encyclopedia of Pirates” can help lead you to them. Do not be discriminatory with what you read, for even in the meanest book may lay untold treasures. That one fact, one sentence in every ten thousand, is what you are looking for, especially as your narrative starts to take form. You’ll have certain plot needs; you will find that history presents them to you, trundled and gussied.

I’m going to recount to you a story of the wonderful and terrible consequences of such a find, and how it relates to a specific project.

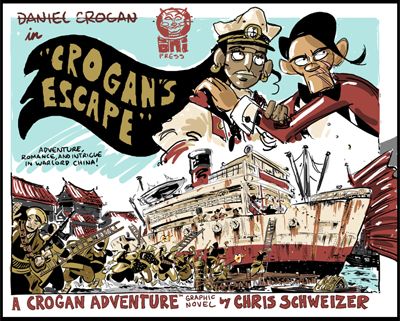

This is one of the Crogan protagonists: Daniel Crogan, a circus performer.

Based on his occupation and the time in which I’ve established he was active – the 1920s – I anticipated that this would be my “pulp adventure” book. Each book, as I approach them, awards me the chance to tackle a different genre. Crime noir, romance, western, coming-of-age, exotic travelogue, war, boy detective… I have a framework that allows for all of these, and pulp adventure has always been near the top of the list of the sort of things that I want to indulge in. One of the elements I love with pulp adventure is the Indiana Jones standard of treasure hunting – an artifact that serves as the story’s Macguffin. Another is the presence of tramp steamers, ugly, ancient hulking ships capable of transporting characters to the most exotic locales.

I knew that I wanted to incorporate these elements into Daniel Crogan’s story, and so devised a solution: he is a performer with a traveling show, E.M. Scufflegrit’s Occidental-Oriental Traveling Waterfront Circus and Curio Museum. The circus and museum uses as its headquarters a tramp steamer, and the curio museum – for which the circus performers are but an advertisement – serves as the purpose for the hunt for rare or historically significant objects. Not unlike Charlie in Charlie’s Angels or the professor in Futurama, the circus’s proprietor, named for a road in Marietta that I pass each day on my way to the college, serves as a means to quickly and efficiently introduce plot goals, thrusting the characters into circumstances ripe with narrative possibility.

This determined, I needed a setting. One mention of “Warlord-Era China” in a book about soldiers of fortune (I was studying the French Foreign Legion at the time) hooked me. China’s Manchu dynasty was overthrown in favor of a democratic republic in near the end of 1911, and became a military dictatorship when Yuan Shikai maneuvered control from its first president, Sun Yat-sen. When Yuan died in 1916, the country’s central government collapsed entirely, leading to a fragmented collection of provinces each ruled by military leaders. The idea of this Chinese wild west, populated by armored trains and bandits and mercenaries of every stripe, seemed the perfect place in which to set my story, and the narrative requirement of the steamer to make port at exotic locales, both to pillage and perform, allowed for it to be so. I had the basis for my book, a point from which to work.

And so I began studying China in earnest. But I could not find a strong reason for the steamer to enter the mainland itself rather than stick entirely to the coastal port cities. My story necessitated one, so as to not allow the protagonists a clear avenue of escape when they fall afoul of a warlord, but I could not find a pragmatic, and therefore believable, motive.

Then I found a picture.

I was working on Crogan’s March, the Foreign Legion installment, and the story featured a scene in which some of the characters fear an encounter with a djin in a haunted cave. A djin – a word from which we derive the familiar “genie” – is a tangible demon or devil in Islamic folklore. And I was curious as to what traditional ideas held their appearance to be. As is the case with most traditional Islamic folklore, representational imagery is rare. The idea that only the Prophet Mohammed is prohibited from being depicted is a new and theologically soundless idea, stemming from the original preclusion of depicting ANY living creature (excepting plants, I believe) created by God, which is why most Islamic art has traditionally been non-representational geometric pattern-work. Therefore, there are precious few pre-twentieth century depictions of Djins.

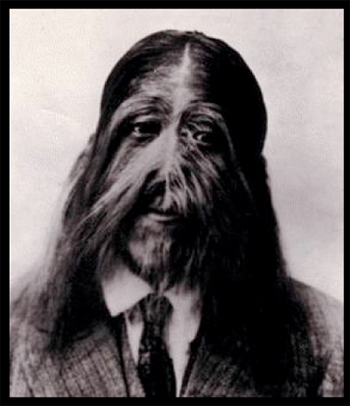

That didn’t stop me from doing a Google image search, however. Among the first few images was this photograph, which sparked my curiosity:

It appeared to be a man affected by Hypertrichosis, and I clicked on the link to find a biography of a man referred to as Su Kong T’ai Djin ("Su Kong" being his title, and the word "Djin" being the reason he came up in the image search). A foundling left at a Shaolin Temple in the Fukien province of China in 1849, he became a student and quickly learned a variety of Kung Fu practices, eventually becoming the grand master of the temple, to the irritation of another master, Chi Tao Su, who under the employ of a military leader took an army to capture the temple. T’ai Djin, rather than losing the temple, opted to destroy it, fleeing with the other monks to Indonesia.

I had my plot device. One of the circus performers – an Asian man afflicted with a skin condition that made him look like a lizard – would quit, the proprietor would, upon seeing a photo of T’ai Djin, who would have been grandmaster in 1920, take the steamer upriver to try and recruit him for the circus, where they would be trapped – the warlord wishing their destruction being the same one attacking the temple in the historical account with the aid of the disgruntled Shaolin renegade.

I read a few articles – most seeming to be variations on one original source – and started writing the story out in full. I finally found the original source of the T’ai Djin story – Shaolin-Do: Secrets of the Temple, by James Halladay and Sin Kwang The,’ and read the pertinent sections, making notes.

My story was loosely plotted, I had my sources – but as I was researching the province and the Shaolin monks in general – I’d sworn to stay away from Kung Fu, as so much of its “history” is pure falsehood and exaggeration, but this was too perfect an opportunity to pass up, and I was becoming very invested in it – I discovered some inconsistencies. The story of the jilted master leading a government army against the Fukien Shoalin temple was almost identical to the story of Bak Mei – only that story purports to have taken place in 1723. Soon other inconsistencies started to manifest themselves. One of the biggest points of concern was that I could find no mention of a Grandmaster named T'ai Djin in what Shaolin records were available, which seemed especially odd given that his position was so very recent (less than a century ago) and that the monks otherwise kept meticulous records.

It wasn’t until I was looking for a gym in which to study Shaolin Kung Fu in order to better inform my approach to this story and its choreography – as well as lose the twenty-odd pounds that have attached themselves to me since I started cartooning – that I found the origins of these discrepancies. Sin Kwang The,' co-author of the book in which my T’ai Djin source originates, is the current grandmaster of the Shaloin-Do school of Kung Fu, a heavily franchised gym with a number of schools in Atlanta. The book seems to be an attempt to historically validate a school whose influences seem to be a hodge-podge of martial arts from China, Korea, and Japan, growing from a school started by The’ in the 1960s, seemingly codified according to the popular dictates of the Kung Fu movies of the time. The photos of Tai Djin are, in fact, supposed by many outside commentators to be pictures of a Chinese circus performer from the late 1900s.

T'ai Djin, as far as I have been able to ascertain, did not exist.

I was devastated. My story hinged on the existence of this man. To be fair, all of my characters thus far are entirely fictitious, and there should be no reason why this would be different, save for the near- unbelievability of him. Even so, my work – which I prize as being historically plausible – was in trouble. I had kung-fu monks despite the notoriously inconsistent way in which they’ve always been presented; I had a larger-than life character no longer rooted in reality – in short, I had a mess.

But the success of the Shaolin-Do schools got me thinking. Maybe there is no historical validity to their claims. But I think of it as analogous to Mormonism. There’s no legitimate historical/archeological validity to the claims made by the BOM pertaining to the Americas, either, but that doesn’t mean it is not successful as a religion and that its true adherents are not moral and religious people, devoted to their faith and excellent examples of what a practicing Christian should be. It is, and they are. Likewise, the students of the Shaolin-Do schools seem to be excellent martial artists. I equate the two because the belief of the school’s students in the face of factual contradiction could only be described as religious. That it has no historical basis does not fall on them as fault, though some would see it done so.

Maybe Sin Kwang The’ made it all up. Maybe he was simply delivering up the story told to him by Ie Chang Ming, purported to be T’ai Djin’s student and the teacher of The’ in Indonesia. Either way, I decided that maybe I should keep T’ai Djin (though I have changed his name somewhat in order to avoid the utilization of what may in fact be a fictitious character given that admission of said fiction on the part of The' could find me legally culpable for copyright infringement) and incorporate this new information into the story itself.

What if, when propositioning the T’ai Djin character to join them, the circus characters receive a rejection secretly motivated by the wolf-faced man’s past as a circus performer and unwillingness to return to the life? What if, expecting a show of force from the monks when confronting the Warlord, our characters find that they are opportunists and imposters, and that the situation in which my protagonists now find themselves is suddenly much more strategically dire? What if, in an effort to save themselves and others, the monks prove themselves capable of the greatness that their future adherents will someday claim? It creates many more story possibilities than the original incarnation, and still stays true to the spirit of history. But had I accepted the first source without question, I’d have missed these opportunities. History, both fiction and nonfiction, is rarely presented without motive, and it is important to read as much as possible, that you might spot these motives and behave accordingly.

In the preface to his 1938 naval biography Forty Famous Ships, Henry Culver drolly addresses the following point:

The business of a professional historian is to extract the data at his disposal, regardless of its source and often without too much attention being paid to its accuracy or authenticity, such material as best suits his personal point of view, rarely bothering to tell the whole truth; or, if he does so, to present it in such a manner as may be dictated by his bias, be that national, political, or literary.

He’s right, and it leads me to a point: the adage that “history is written by the victors” has validity, but losers can write history too, and often do. And in delivering the facts in a way that supports one’s political, social, or literary thesis, the writer succeeds where his or her cause may have failed. Writing history IS victory.

And this predetermination of thesis permeates nearly all scholarship, usually resulting in two strikingly different academic bases regarding each period. My first experience with this was while working on pirates. On one side, I found work after work proclaiming that pirates were the precursors to modern democracy, being the first self-governed and self-legislative body in the Americas, a body in which any man could rise to a position of authority based on merit rather than birthright, chosen by his peers through a vote. By choosing to self-legislate (pirate codes and laws), pirates can be seen as the proactive victims of historical circumstance, casting off the shackles of societal oppression to enjoy the first true freedom experienced in large numbers.

On the other, I found book after book, article after article, espousing the certainty that pirates were vicious criminals, murderers who attacked civilians and stole from them all their worldly possessions, their dignity, and, in many cases, their very lives. They sank incredibly expensive ships, tortured prisoners, kidnapped innocents, and all but destroyed the economy of Western Europe by making trade, commerce, and investment in shipping or overseas markets impossible. They were not dashing movie heroes but terrorists, rapists, thieves and killers who irrevocably ruined the lives of virtually everyone with whom they came in contact.

My opinion is that both of these arguments are entirely true, though their usual proponents seem to find them mutually exclusive, as is often evident by a forward or introduction seemingly designed to preemptively refute the other stance. My narrative presents both – the horror and the romance – in an effort to accurately depict the time. This has been the thesis from which I have approached all of my stories. I take the two divergent opinions and present both. Maybe this is wishy-washy. Maybe it shows a lack of backbone on my part. But I believe both camps in most instances, and feel a duty to share that with the audience, giving them a basis from which to accept or dispute either side. I find that story, attributing a human dimension to a principle, better illustrates it than any other means of intellectual conveyance, and makes dismissing one side or the other out of hand all but impossible.

I write these stories, but, as I said, I draw them, too. And one of the hardest things is finding good visual reference. The name of this lecture is “Benjamin Franklin’s Pants,” and it stems from something said to me on the phone by another cartoonist. I remember when it was said – I was in the garage, moving some lumber, and talking on speakerphone. But I cannot for the life of me remember who said it. I’ve asked a few likelies, but each denies it, or attributes it to me, and so I cannot thus far give credit where credit is due. But the gist of it is this: You can read a 600-page book about Benjamin Franklin and nowhere find a description of his pants.

This is true, and a bane to artists working on historical fiction. Sometimes there is detailed prose description; more often there is not. Even in the instances where descriptive prose is employed, it can often be difficult to accurately illustrate it. So finding visual sources is a genuine goal.

In some instances, it’s easy. Military uniforms are pretty stringently reproduced in a variety of books, and those books, while sometimes expensive, are not difficult to find. There are some six or seven hundred volumes of the Osprey Military History series, which recounts uniforms of just about every variation and campaign. Equally documented is the clothing of the rich and of royalty. The problem is how to address the visual aspects of things that are not well-documented.

The rich have always had a habit of sitting for paintings or sculptures in their most fashionable garb. As such, we have plenty of first-person, period depictions of them. The same goes for architecture, and ships, and anything else. The fancy, the notable, the opulent – these are what gets put down on canvas.

The big problem is that your story may not deal exclusively with this upper-tier of society, and finding the garb of peasantry, interior images of a hovel, and fishing boats on their last legs is an unlikely prospect.

Luckily, such things remain more or less consistent. The clothing worn by a poor Algerian at the turn of the twentieth century is not much different from what he or she might have worn half a millennium earlier. The differences in dress for a peasant in 1800 in rural England is not strikingly different from that of 1700. A ramshackle cottage rings true in pretty much any era. But finding that basis from which to begin can be truly nightmarish.

Museums are a good place to start. While it is generally the noteworthy that makes display, anything of antiquity merits inclusion, and so the tunic of a plebeian or the shawl of a seamstress might make their way into a glass case.

Theater books are another. Of the hundreds of “History of Costume” books, quite a few deal with the lower echelons. Most employ historical experts at the preproduction stage, and while they may be vague in their worded descriptions they can be meticulous with the practical application of their study – film costumes can be quite accurate, especially in ones notable for their adherence to fact.

The best reference that I have found is a surprising one, and one which I discovered entirely by accident: reenactors. If one has done his or her base research, and knows what questions to ask, then reenactors are the best source of information that one can find. I did a signing in Greensboro, North Carolina, and the staff of the store took me, my wife, and my daughter to dinner afterwards. At the restaurant, we encountered a number of folks dressed in Revolutionary war uniforms. They told me that there was a reenactment going on the next day, and so we extended our trip and went.

There are few sources more beneficial than a group of three hundred people so obsessed with the minutia of their period that they will lose sleep overly an improperly holed button, all eager to share that knowledge. They were willing to go through their accoutrements piece by piece, to discuss a myriad of details, to walk me through the loading of a musket, the attaching of a bayonet, the warming of a cooking pot. A particularly notable encounter was with a group of folks dressed in green, who I recognized as being Jaegers – Hessians skirmishers notable for their comfortably in wooded theaters of action.

One of my characters – a very prominent one in the new book – is a Jaeger captain. And though nearly all pictures of Hessian troops during the American War for Independence had impressive mustaches, the one picture of a Jaeger that I’d found was curiously absent this trichotic adornment. I asked the Jaeger reenactors about this, and they said that the image in question was spot-on; the Jaegers were recruited primarily from an area of Germany heavily populated by Turkish emigrants, whose practice it was to flaunt large mustaches. The native Germans of the region, not wanting to be mistaken for Turks, chose to abstain from the practice so prevalent throughout the rest of Germany. This was a tidbit of information that I, having read one full book on the Jaegers and a few others on Hessians in general, had not stumbled across, and so this encounter was very helpful. My character went from having a moustache to having none, and subsequently falls more cleanly into accurate historic representation.

Reenactors are only one aspect of the “hobbyist” side of history. Hobbyists, moreso than professional historians, seem to concentrate their attention on the practical application of historical knowledge, which is exactly what you need. A book on historical model ship rigging is actually of far more value than one on the rigging of historical ships, precisely because it approaches the subject not from the standpoint of an observer but that of a participant. You will see simple and detailed diagrams showing how each piece attaches to another, in a way that might allow you to build it – or draw it, or model it in maya, or animate it, or whatever you may choose to do. Costumes, buildings, transport, weaponry – the hobbyist press will likely help you more in these things that you would ever expect. Find out if your period has enthusiastic armchair historians, reenactors, modelers. They can turn you on to any number of great books and sources that you may otherwise miss entirely.

My books are “historically plausible.” I try to keep as true to the period as I’m able, but my characters and events are fictitious. The primary reason for this is that I get easily frustrated by books or films that feature real events and use fictional protagonists in cases where the protagonist is responsible for causing the events deemed so noteworthy by history to come to pass. As a rule, we have accurate reckoning of these events, and we know who did what, and which key players were involved. Thus, the fictional character notably changes how the history came to pass, and thus its very nature. Sometimes this is not the case; George MacDonald Fraser’s Flashman Papers series squarely plants Harry Flashman into pretty much every important and well-documented military engagement of the last half of the nineteenth century, and quite a few in the decade preceding it, and does so with such narrative dexterity that not even the most ardent student of those engagements would deign to contest Flashman’s presence. Bernard Cornwall’s Sharpe series, however, regularly has Richard Sharpe performing feats knowingly attributed to other figures.

This is not to say that these are not engaging books, but the conceit is often a strain to bear. To his credit, Cornwall does a fine job making the case for the plausibility of such action.

But what if one is dealing with true historical figures, attributing clear and human motives to their actions and fictionalizing the drama? This is something else entirely, and leads to one of the key questions asked when dealing with historical fiction. When is it all right to stray from fact?

That one must stray occasionally should be a given. Adhering strictly to the letter of accounts, while sometimes possible, usually leads to boring, uninspired stories. You must remember that your job is that of a storyteller. You are crafting a narrative, and if the truth does not make a good one it is your obligation to reshape it for the sake of your audience. But reshape it you must; you must not through away the facts, you must present them in a way that is historically palatable. Though no one from a thousand years ago will sue you for libel, you have a moral obligation to fairly and accurately depict people who have actually lived. If you do choose to stray from fact, you must study those figures more closely than any others. Their variations MUST be the result of CIRCUMSTANCE, not character.

The changes should occur when you reshape the order of events, or offer new avenues through which the figures might act. But you must ask yourself “how would this person behave if offered this choice or forced into this situation?” You have done your research, you have learned that person’s history, and you should be able to make an informed and clear decision. In these instances, you will prove both your capacity as a storyteller and your devotion to the truth, for truth is not facts; it is spirit. Stay true to the spirit of your characters, the spirit of your period, and your audience will forgive you the occasional narrative off-roading.

I’ll conclude with one of the best and most frequently cited examples of this sort of thing – 1966’s Khartoum.

It’s the story of the siege of Khartoum in the 1880s, as British officer Charles “Chinese” Gordon, played by Charlton Heston, tries to hold off the massacre of the Egyptian citizens inside the walls by the army of the Mahdi, played by Lawrence Olivier. Near the climax of the film, Heston slips out of the besieged city in the dead of night, making his way into the Mahdi’s camp for a face-to-face meeting to determine what avenues the forces may allow each other to take. It’s a wonderful scene, and a great interplay between two of the cinema’s finest actors… and it never happened.

But that’s okay! Chinese Gordon was notoriously courageous… I’d venture to say “reckless,” but for its negative connotations, and it would not be a stretch to expect that he would’ve undertaken such a venture had the opportunity presented itself. It is true to the spirit of Gordon. And we know the Mahdi to be a man respectful of Gordon, and of the enemies whom he deemed worthy of such respect. That he might allow Gordon safe return to the city is not a deviation from what we know of his character.

Perhaps most importantly, we know how the dramatized conversation might have gone. During the siege, Gordon and the Mahdi exchanged numerous letters, each feeling the other out, each trying to find the best long-term solution to their stalemate. And it is these letters that serve as the basis for the dialogue of the scene.

This is strikingly different from films which bring Elizabeth the first face-to-face with Mary Queen of Scots, her cousin who was determined to usurp the English throne. Fraser, author of the aforementioned Flashman Papers, notes the impossibility of such a pairing in his 1988 book The Hollywood History of the World, easily the best book on period pieces one can find. Elizabeth went through great lengths to avoid EVER meeting face-to-face with Mary, her reasoning being that she knew that if Mary’s attempt at a Coup ever came to fruition, she would have to order either her assassination or execution. Elizabeth had heard tales of Mary’s charm, her grace and beauty, and her familial similarities to Elizabeth, and the queen was certain that, should she ever meet Mary, she would never be able to follow through with a death order, which she must be able to do for what she deemed the good of the country. Therefore, the numerous films in which the two meet do a striking disservice both to history, to Elizabeth, and to Mary.

Know your characters. Know your period. Be true to them in spirit always, and in fact when you can.

Thank you so much; I now welcome your questions.

That's it! I don't REALLY welcome your questions. Remember, this was a talk I gave. Eh, I guess I welcome your questions.

Excellent article! Your attention to period details and dramatic storytelling are what makes the Crogan stories so great to read.

ReplyDeleteAnd now, the nitpick, since we're talking about accuracy:

It's "social mores" (mores being a Latin word meaning 'customs') not "morays" (which are eels).

Thanks, Norman! I can't remember if that was a phonetic spelling to ensure correct pronunciation, as this paper was originally intended to be read aloud, or if I'm just a nitwit. I expect the latter.

ReplyDeleteI'm leaving it in because otherwise our comments wouldn't make sense, but I'll certainly fix it in the document itself.

Dedicated to the Editors Note feature of the Claims Intelligence Report brought to you by The Claims Pages.

ReplyDeletefor more information: claims pages newsletter